Elena M. Watson

A few words

about Elena Watson (1958-1994), by Bill Ruehlmann, Book

Columnist. Bill is a mass communication professor at Virginia

Wesleyan College, Norfolk, VA.

(Originally

printed in The Virginian-Pilot, reprinted by permission of the author)

The skeptical writer was equally wry on Unidentified Flying Objects: "The size of the universe is so huge, and the time span and the distances so vast, that it's ridiculous to think if there were life somewhere that they would waste all this time just to buzz the Earth and pick up a couple of hicks in Mississippi."

And she was just as unblinking about her own battle with progressive disability.

"The muscular dystrophy is a major inconvenience in my life," Elena said, "but it's pointless to whine about it. You live with it. Not long ago somebody asked me if the prognosis means I'm going to become a vegetable.

"I said yes -- broccoli."

She had this thing about mermaids. Elena kept a small one above her computer keyboard, and I think it was a clue. MD put her out of her element in the physical world; but in the cosmos of ideas, and in communion with her associates, she swam free.

Sometimes, upstream. A professional conjurer pal of hers once noted with precision that she was "fiercely rational." In that, she was tough; she stood up fearlessly to fraud and pretense, in person and in print.

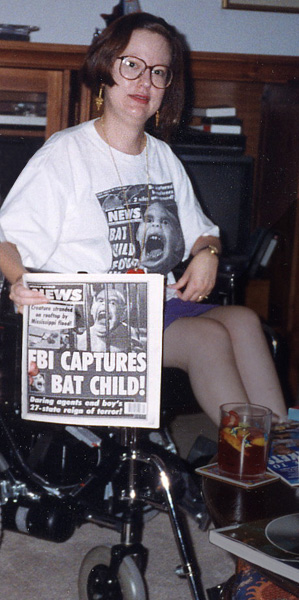

Toward the end Elena went about the world in a motorized wheelchair, defiantly unconfined at the keyboard to Internet and editor of the National Capital Area Skeptical Eye, a newsletter serving 300 critical thinkers banded together for the sole purpose of poking holes in hooey.

She felt that a substantial number of the more academic membership were "humor-impaired" and set about doing something about it. The consequence was a lively and literate publication that drew from a wide range of offbeat sources on unscientific misapprehensions, from scholarly journals to supermarket tabloids.

She loved to ponder the implications of such compelling Weekly World News headlines as "EARTH'S WATER SUPPLY CAME FROM DINOSAUR WEE-WEE."

Elena, who held a degree in psychology from Christopher Newport College, wrote a good book titled Television Horror Movie Hosts: 68 Vampires, Mad Scientists and Other Denizens of the Late-Night Airwaves Examined and Interviewed (McFarland, 242 pp., $29.95). She documented the low-budget likes of Ghoulardi, Sir Graves Ghastly and Dr. Maximilian Madblood. Why?

"The shows," she said, "offered a certain energy, originality and creativity the slicker network stuff lacked. They were not mass-produced. There was an underlying level of subversion to them."

As indeed there was to her. Elena was an inveterate enemy to unexamined opinion, superstition and smugness. For her, the daughter of a minister, truth was a sword that protected people from every sort of snake oil, be it totalitarian government or sneak-thief 900 numbers.

"There are telephone hot lines that advertise themselves as providing a psychic friend who really cares about you," she said.

"They care about you for $4 a minute, which adds up fast. Meanwhile, there are a lot of people out there who don't have friends, who are lonely, who are ill.

"I think they're being victimized by things like psychic hot lines."

Instinctively, she identified with the underdog. In some ways, she had been one. As a child her schoolyard peers had not been kind to the short girl who walked differently. "I've always had sort of an outsider status," Elena said. "It made me a little bit cynical about people. I just had a sense that you can't always believe everything you hear."

That sense extended to critical judgments. Performers and films long since consigned to "B" status and below were often tops with her. It was never production values that impressed Elena in a movie; it was flair.

Among her favorite actors was Peter Lorre, whose ability often transcended his material; on the wall beside her computer, Elena kept a photograph of him as Mr. Moto, the bantam superspy of late 1930s films.

"Moto was cool," she said. "He juggled, did magic and performed martial arts. He played the fool for people, but he was a very logical guy who knew everything that was going on."

Like Elena. She loved magicians, too. They fooled the public but made no bones about the hustle.

She loved only one thing more, and that was her husband, John S. Pickel, a project engineer at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard.

One day Elena fell and did not get up again. She was 36 years old. She left behind an extraordinary example of enduring wit and stubborn dignity that provided powerful testimony for the human spirit. Leave it to Elena to see old things new.

No one who knew her will ever forget her.